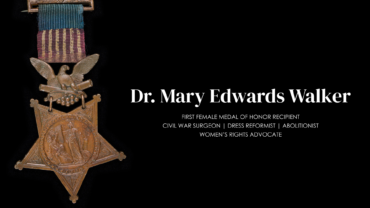

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker: First Female Medal of Honor Recipient, Civil War Surgeon & Women’s Rights Advocate

The Dr. Mary Edwards Walker exhibition invites you to explore the life and legacy of one of Oswego’s most important historical figures. Come see Dr. Walker’s U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor in person, and learn about the woman ahead of her time on women’s suffrage, dress reform, and more.

About the Exhibition

Location: 2nd floor, Temporary Gallery

When: June 8, 2024 – Ongoing

Exhibit designed by Evelyn Frederiksen

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was a Civil War surgeon, advocate for women’s right to vote, labor and dress reformist, and abolitionist, among many other titles. While she is most well known for being the first woman to receive the U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor, she is rarely honored for her never-ending commitment to fighting for the rights of all peoples.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was born in 1832 in the Town of Oswego. She grew up on her family’s farm at Bunker Hill, often assisting in general farm chores. Her parents, Alvah and Vesta Walker, were considered “free thinkers” and were extremely progressive for the time. They encouraged their children to question authority and restrictions, especially laws and regulations that resulted in discrimination against certain groups.

From an early age, Dr. Mary Walker was encouraged to dress in a way that favored comfort and utility. Her mother disapproved of the use of corsets—she believed they were too constricting and threatened the health of women. This belief informed many of Mary Walker’s opinions later in life.

Walker’s parents also stressed the importance of education, and sent all of their daughters to be educated at Falley Seminary in Fulton, NY. Dr. Walker went on to study at Syracuse Medical College. She graduated with honors as a medical doctor in 1855, just six years after Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to graduate with a Medical Doctorate in the United States.

The Civil War

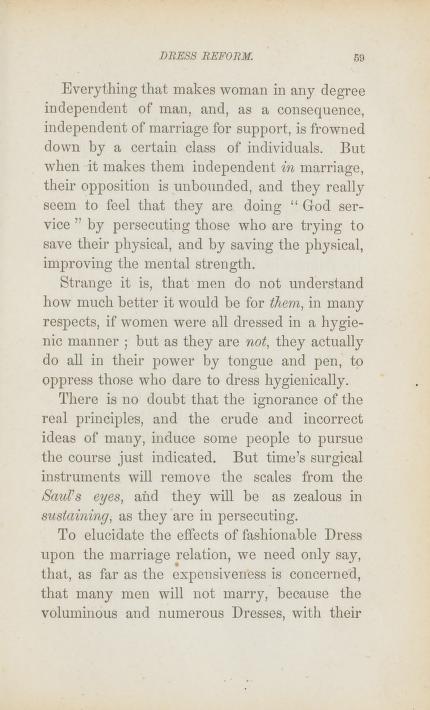

Illustration of the Battle of Chickamauga, 1863. Dr. Walker worked as an unpaid field surgeon on the Union front lines for battles such as this one. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Dr. Walker made her way to Washington D.C. to offer her services as a surgeon to the US Army. Although she had several years of experience as a doctor, the Army would only allow her to be a nurse because she was a woman. Refusing to demote herself, she instead offered her services to the Union Army, working as a volunteer surgeon in the field.

After two years of volunteer service, Dr. Mary Walker was finally accepted by the U.S. Army as a “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (civilian)” in 1863. During her time as the first female U.S. Army surgeon, she served the Army of the Cumberland and the 52nd Infantry of Ohio.

While serving on the front lines, Walker was captured by Confederate soldiers and held as a prisoner at Castle Thunder in Richmond, VA. While imprisoned, she continued to care and advocate for wounded prisoners. She additionally refused to wear the clothes “more befitting of her sex” offered to her. After four months of imprisonment, Dr. Walker was released as part of a prisoner exchange.

For her services in the war, Dr. Walker sought retroactive payment from the U.S. Government. Because she was considered a civilian, and was never a commissioned officer, it was determined she was not eligible for compensation. In lieu of payment, on November 11, 1865, President Andrew Johnson awarded Dr. Mary Walker the Congressional Medal of Honor for “devot[ing] herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the field and hospitals, to the detriment of her own health.”

Activism

After the war, Dr. Walker traveled through England, France, and the United States to give lectures about her war experiences, women’s suffrage, and dress reform. While audiences were generally receptive to her theology in Europe, she faced difficulties in the States. Her speeches did not draw nearly as much attention, and subsequently brought in less money.

In 1871, Walker published her first book, HIT. There, she delved into topics such as dress reform, marriage and divorce, labor, religion, among others.

She spent most of the 1870s lobbying in Washington, D.C. for women’s suffrage and continuing to write.

A non-conformist at heart, Dr. Walker was no stranger to getting in trouble with the law. She continued to wear trousers her entire life, and was arrested many times for “public indecency.” Other times, she was accused of “masquerading as a man.” She responded to this accusation, stating, “I do not wear men’s clothes, I wear my own clothes!” Walker believed that clothing should “protect the person, and allow freedom of motion and circulation, and not make the wearer a slave to it.”

Dr. Mary Walker fought her entire life for the rights of women. While she rallied for women’s right to vote, she opposed fighting for an amendment to the constitution to allow them to do so. She believed that the constitution already afforded women the right to vote—their rights were simply being denied.

Walker’s perspective put her in direct opposition to the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement. Adamant that women just had to demand their votes be taken, she would interrupt suffrage meetings to argue for her position. In 1901, The Pulaski Democrat described her as “characteristically obnoxious”. Walker would attempt to join the Women’s Suffrage Association, however her application and dues would be rejected likely because of her stubborn defiance against the Association’s activism.

Later Life

1917 was a difficult year for Dr. Walker. That year, Congress approved a new standard for Medal of Honor recipients, which retroactively struck 911 recipients—including Walker—from the Medal of Honor award list. These individuals were commanded to return their medals. Walker refused. Instead, she wore it for the rest of her days, which was considered a misdemeanor.

Dr. Mary Walker died on February 21, 1919, after a long illness likely stemming from her accident on the Capitol’s steps. Later that year, the 19th Amendment would be passed by Congress, allowing women to vote in the United States. Although she staunchly fought against the need for an amendment, Walker would die just a year before being able to vote legally in U.S. elections.

Dr. Walker’s medal has since been reinstated through the efforts of her grandniece Helen Hay Wilson (a fascinating story in itself!). And in the modern era, her life continues to be recognized. In 2023, Fort Walker, formerly known as Fort A.P. Hill, was designated in Dr. Walker’s honor. Additionally, in 2024, the U.S. Mint released a special edition quarter highlighting Dr. Walker in their American Women Quarters™ Program.

This exhibition is the result of the Mary Walker Campaign, a $36,000 capital campaign to get Dr. Walker’s original Medal of Honor permanently displayed at the Richardson-Bates House Museum. An esteemed thank you to our sponsors and contributors to this exhibition; it is with your help that we are able to preserve her legacy.

This project was funded in part by a grant from the Richard S. Shineman Foundation.

Oswego County Legislature

Charles Courtland Hall, Jr. Trust

Jennifer Hanley

Barbara Hanley

Michael & Edie Nupuf

Chris Gagas

Elk’s Lodge #271

William Joyce

Doug & Naomi McCracken

Albert & Victoria Sabin

Edward & Diana McKenna Campbell

K-9 Grooming & Pet Motel

Bardan Construction Co

Richard & Susan Axtell

Celia Sgroi

Matt & Katie Beaudry

Fulton-Kayendatsyona-Fort Oswego Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

George Allen

Dennis & June Ouellette

Daniel & Linda Ruddy

Joey Sweener

Richard H. Sivers

Mike & Carol Fitzsimmons

Joyce Cook

Dee Dee Murray

John & Ann Allen

Jeanne & Michael Brown

James Scanlon

Carol & Jim Balmer

Barbara & Douglas Caruso

Nan Moore

David & Debbi Murray

Robert & Anne Morgan

Advanced Information Services

Dr. Natalie Woodall

Linda Samuels