This essay was originally published in the 1942 OCHS Yearbook. Please note that this essay was published over 80 years ago. While still useful for general education, language may be outdated and at times offensive. The Oswego County Historical Society does not stand by the language used in this essay. All photos were added in 2024 when this article was uploaded to the web. To view the original document, please visit NYHeritage.org.

Paper Read Before Oswego County Historical Society at Oswego, February 16, 1943, By Miss Frances Eggleston of Oswego, Collector of Early American Glass

In the abundance which has been provided for us for many years and in the mammoth and mechanical production of our great industrial enterprises we are likely to forget the beginnings of these industries, the potter’s wheel and the glass blower’s pipe. In the beginning these were arts, not industries and it is as arts that history regards the budding of these enterprises in our shores.

Cleveland Glass Ranks Well

Within the boundaries of our Oswego county there was established and carried on at Cleveland a glass house, the product of which ranks well with all other industrial efforts both in interest and in individual artistic expression. Cleveland is suituated on the north shore of Oneida Lake in the extreme southeastern corner of Oswego county and its glass industry is so closely connected with several houses in existence at the same time in Oneida county to the east, that from the point of view of glass history it is inevitable, when one explores the history of glass making in Oswego county, to consider also the Oneida county factories. Indeed to arrive at a proper conception of the subject we must consider the establishment and progress of this art in the entire country. This is the pathway which leads up to our door.

For those who collect old glass, there is in addition to the pride of possession the fascination of historical and social significance; for each piece which has survived is tangible evidence of a way of life, of a stage in social and industrial development and frequently of stirring events. Whether the event was only of passing interest or one of historical importance the glass commemorating it is a link with the past and one finds a thread of continuity of techniques and forms which stretches from antiquity to the present.

Fire Turns Sand Into Glass

The making of glass consists of the transmutation by fire, of solid opaque grannules of sand and alkali into a liquid state and back again into a brittle transparent solid. Glass beads made about 2000 B.C. were found at Thebes and Egyptian glass may have antedated that. By the second or third century glass household articles were in common use and houses had glass panes in their windows. By the 15th century the Venetians enjoyed a virtual monopoly of the glass trade. So jealous were they of their formulas and techniques that by the middle of the 15th century a statute was passed providing that any workman who carried his craft into a foreign country and refused to return should be killed by an emissary appointed for that purpose. Artisans who tried to escape and sell the secrets of the Venetian glass workers were stabbed by the medieval Gestapo. One blower who had been offered a fabulous bribe by the covetous Court of France was killed at the very gates of Paris.

As time passed other European countries became proficient in glass making. In France, the Lowlands and to some extent in England glass workers from Italy taught their techniques to native artisans. When glass houses were established in America they were manned by workers who came from nearly all countries in which glass making had been highly developed. In making glass of any kind these glass workers quite naturally followed the methods and styles of their native lands. So it is hardly surprising that many years passed before all the influences blended into something approaching a native American expression.

About a year ago Mr. George V. McKearin and his daughter Helen published a book called “American Glass”. Mr. McKearin is the outstanding authority on this subject and I quote from him rather extensively. As to the early types of glass—he says:

“Prior to 1920 there were few students and collectors of American glass, consequently research was limited. The most ambitious project was that of John B. Kerfoot and Frederick William Hunter who conducted extensive research into the life of William Henry Stiegel and his glass manufacturing from 1763 to 1774 at Elizabeth Furnace and Manheim, Pa., and also of Casper Wistar and the glass house he founded in 1739 and which he operated until about 1780. The results of their research and conclusions as to the nature and characteristics of the Stiegel and Wistar products published in 1914 marked these centres as the fountain heads of two distinct streams of tradition in glass blowing and decorative technique in America.”

America’s First Factory Made Glass

It is interesting to know that the first factory erected on United States soil made glass and glass was our country’s first export of manufactured goods. To substantiate this we know that the first settlers in America landed at Jamestown in 1607. This group did not meet with success and in 1608 a second group was sent by the London Company. This included eight glass men, Dutch and Polish. The company hoped to establish a thriving glass industry nearby, not because the settlers needed glass but because England did. They set up a crude glass furnace in the woods about a mile from the settlement.

Hildebrand says: “These pioneers made so many beads for trading with the Indians that the glass currency became inflated and the colonists started shipping beads to England at less than ceiling prices. Old records fail to tell how long this first commercial enterprise lasted, but the pick and the shovel have delivered to museums specimens of the beads and remnants of the furnace bricks and clay pots.”

Under the later English rule the colonists were not encouraged to make any commodity such as glass, as it was feared it would interfere with the importation of the foreign product and before the Revolution glass was one of the articles taxed by England.

Nearly all American glass factories were established primarily for the manufacture of window glass. But these factories provided receptacles where left over portions of glass were thrown, which the glass blowers had the privilege of using for their own purposes. It is these pieces of so called “off-hand” glass that collectors prize.

Watson Friend Of George Scriba

Now to trace the history of glass manufacture which finally led to the village of Cleveland.

For much of the following information I am indebted to Stephen VanRensselaer’s book on “American Bottles and Flasks.” Mr. VanRensselaer, being a descendant of one of the early glass men, has had unusual opportunity to assemble these facts.

In 1786 or 1787 in Sandlake, near Albany, a glass works was established. About the year 1788 Leonard de Neufville, Ian Heefke and Ferdinand Walfahert, the proprietors of the Dowesbourgh glass works near Albany—which undoubtedly is the same as the Sandlake—appealed to the people of the state of New York to sustain their manufacture of glass. They set forth that the state was annually drained of 30,000 pounds Stirling for this necessary article which they could manufacture and which excelled in quality English glass. These works were visited in 1788 by Elkanah Watson. Watson was a friend of George Scriba and his name appears frequently in connection with Scriba’s early activities. Watson’s acquaintance with the founder of this enterprise gave him the following information which his son published in the memoirs of his father:

“Elkanah Watson proceeded eight miles from Albany to the new glass house erected by John de Neufville, a former correspondent of his, and once a resident of Amsterdam. John de Neufville had been the negotiator of a treaty made by Holland with the American Congress, which primarily produced the war between Holland and England in 1781. He commenced business with a hereditary capital of a half million, sterling, and lived in Amsterdam at his country seat in affluence and splendor. He sacrificed his fortune to the cause of American independence. The fragments of his estate he invested in the enterprise of establishing this glass factory. Elkanah Watson found this gentleman, born to affluence, living in a solitary place, occupying a miserable log cabin, furnished with a single deal table and two common chairs, destitute of the ordinary comforts of life.”

De Neufville’s Influence

This factory, which de Neufville —an American patriot, had established as his last hope of success in life was soon deserted for want of funds to carry it on. But an effort was made to reopen it in 1795 with more or less success. In 1806 the legislature passed an act to incorporate the stock holders of the Rensselaer Glass Factory; as it was then called. The incorporators were Jeremiah Van Rensselaer, John Saunders, Elisha Jenkins, Elkanah Watson, George Pearson, James Kane, Thomas Frothingham, Frederick Jenkins, Rensselaer Havens and Francis Bloodgood. The capital stock was not to exceed 100 shares at $1,000 each.

They had to import skilled employees. Mr. William Richmond, a Scotchman, was superintendent of the works and he went abroad to procure workmen. Disguised as a mendicant with a patch over one eye, playing upon bag-pipes he wandered through the glass district of Dunbarton in Scotland and engaged his blowers to cross the sea. With great difficulty they hid their tools on shipboard, as it was a penal offense for glass blowers to leave Scotland. In this Van Rensselaer factory the crown blowers were Scotch but many cylinder blowers were German. The latter were a poor set—intemperate and extravagant.

In 1816 a fire was started by sparks from the pipes of some of the blowers who were playing cards on a pile of straw in the packing room and the cylinder works were burned down. In 1818 these were rebuilt and continued functioning until 1853.

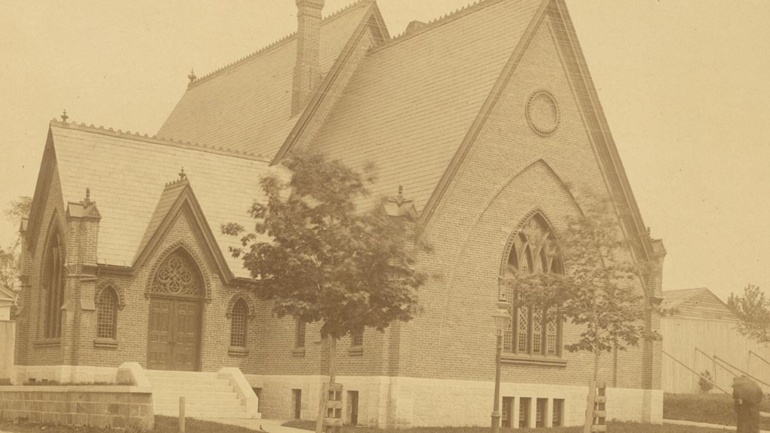

Cleveland’s First Works Opened

In 1840 However, the same company in 1845 had built a factory at Durhamville in Oneida county. This glass house was still doing business in 1878 under the name of Fox & Co. And about four miles below Durhamville, at Dunbarton, which was named from the Scotch village where the blowers were recruited, a factory was established in 1802 which remained in existence until 1890. In 1878 this glass works was owned by Monroe-Cowarden & Co. George Cowarden was a son-in-law of Anthony Landgraff, who with his father-in-law and his brothers-inlaw came from the village of Vernon to Cleveland in 1840 to establish the Cleveland Glass Works.

Factory Built Upon Best Sands

Although sand suitable for making glass was discovered as early as 1813 several miles west of Cleveland, its existence in the neighborhood of that village was unknown and for the first year after establishing his works there Mr. Landgraff boated his sand from Verona, upon the south shore of Oneida Lake. He discovered in 1841 that his works were located upon a bed of sand far superior to that he had been using. In consequence of this discovery two other glass factories were established in the village and a large amount of sand was exported annually to other works in New York state and Canada. In fact the quality of the Cleveland sand is so superior that the Corning Glass Works of Corning, N. Y., which made the giant reflector for the Mt. Palomar Observatory in California has used the product of the Cleveland sand pits in recent years, especially for the making of fibre glass.

There is now living in the village of Cleveland Mrs. Marion Morenus whose husband was identified with the glass works there and whose brother-in-law, Eugene Morenus, was the manager of the factory in its last period. Mrs. Morenus has sent me a pamphlet which was published in 1903 upon the celebration of the burning of the mortgage which previously had been placed upon the Cleveland glass house. I have selected the outstanding and consecutive facts from the pamphlet and present them to you.

Hemlock, Not Sand, Invited New Works

The first period in the history of the window glass industry in the village of Cleveland began in 1840, when the first factory was built by Anthony Landgraff and his sons and his son-in-law, George Cowarden. The family came from the village of Vernon, Oneida county, where they had conducted a window glass plant for several years; but the scarcity of hemlock, the fuel used for melting the glass, compelled a removal of the factory and Cleveland was selected as the new site. The tiny village of Cleveland was then surrounded on three sides, except along the lake road, by primeval forests in which only here and there an opening had been made by the axe of the pioneer. On the remaining side stretched the glistening waters and broad expanse of Oneida Lake rich in historic association and Indian tradition. The whole region was a sportsman’s paradise.

The village dates its development and growth from the building of the old Eagle Tannery in 1834, so that when the glass factory came six years afterward there was a thriving little village to greet it. Lake and Bridge streets were built up almost as compactly as they are now, but on the north the forest encroached closely and the glass factory was built almost, if not quite, in the woods. The fuel then used exclusively for melting and flattening was hemlock wood, cut f4ne, about three feet in length and dried in brick ovens; the first wood cut for this purpose was piled against the drying house by the choppers, so nearby was the forest.

Early Works Had Small Capacity

The new factory buildings were large and substantial for the time, but the melting furnace was only about six by eight feet on the inside and the melting pots little larger than good sized water buckets. A single blower could carry and place them in the tempering ovens. Their capacity was about three hundred feet of glass, but as both double and single strength was then only half their present thickness, these ancient pots held only about one hundred and fifty feet. The cylinders were mere pygmies by the side of the huge rollers of today, but they were opened offhand without the aid of pole or crane. Each blower gathered, blew, flattened and sometimes cut his own glass and the tending boys—now gatherers—were merely water boys and roller carriers. Those were days of long fires and many weary working hours for the blower, but the wages were good even in those days, averaging more than a dollar a box. The manner of selling the glass was in keeping with the character and primitive ways of small, local, independent manufacturers. In the middle of the last century Oneida Lake was connected with the Erie canal system by a side-cut, and it was customary during navigation to load a canal boat with glass and peddle it out in the towns and villages along the canal from Troy and Albany to Lockport and Buffalo, often in the way of barter for store goods and other supplies.

The Landgraff family conducted this factory, the old Cleveland Glass Works, for twenty years and then after a brief period under William Sanders, it passed in 1863 into the hands of J. Caswell and Crawford Getman. In 1877 Mr. Caswell retired and Mr. Getman continued the business alone for many years.

Second Works Established At Cleveland

In 1851 the Union Glass Factory was built by a stock company composed mostly of Cleveland citizens, but after a year or two it was reorganized and came under the control of William Foster, Forris Farmer and Charles Kathren who ran it with success for more than twenty years. Then for several years this factory was idle and after several changes it was sold in 1882 to Crawford Getman, the proprietor of the Cleveland factory who conducted them both until 1889 when he sold both plants to the United Glass company. This company conducted them both until 1893 and the old factory a few weeks in 1894 and then owing to the hard times closed them down, thus completing the first period in the history of glass making in Cleveland.

The second period was a short one. In the spring of 1897 the United Glass Co., at great expense, converted the old Cleveland factory into a model and modern tank with an electric plant attached, and with every facility but cheapness for making window glass. But their two fires were short and in the fall of 1899 they sold the plant to the American Window Glass Co. which promptly closed it for that blast and during the next one operated it for little more than three months and then closed it down apparently for good. This ended the second period.

Cleveland Boomed In Glass Period

The forty years from 1834 to 1874 covered the most prosperous days of Cleveland. With its large tannery, two glass factories, numerous saw mills, its brickyards, chair factory, wagon shops, lake and canal traffic, it was a busy and bustling place, full of picturesque life and incident. The tannery and glass factories consumed great quantities of bark, lumber and wood and mingling with the residents of the village, with its business men, canal men, tannery and glass workers, were the men of the farms and woods, lumbermen, bark peelers, wood choppers and hunters, forming a motley population of various races and occupations. But one by one these various industries dropped out or were abandoned and finally nothing remained but the glass industry.

Two Veterans Seek to Save Industry

The glass works, too. would have gone but for the fact that Cleveland had among her residents two veteran glass manufacturers and managers, Crawford Getman and Eugene Morenus who were experts in the business and who believed that under proper conditions and good economical management it could still be made to pay in its old home. In the spring of 1901 had come the wage settlement which struck out the differential of ••even and a half per cent which had heretofore prevailed in favor of the Cleveland district, and the elimination of which made it unsafe, if not unprofitable, for the ordinary stock company or corporation to make glass in Cleveland. Mr. Getman and Mr. Morenus turned to the glass workers and urged them to form a co-operative company, promising that they and the citizens cene-ally would aid in the undertaking. Attorney James Gallagher formulated the plan of a worker’s co-operative corporation which would enable the workmen to be their own employers, and to a great extent regulate their wages and profits by the conditions of the trade. Under Mr. Gallagher’s counsel and aid the company was organized and incorporated as the Getman Window Glass Company.

Sherman Act Closed Works

This last company continued in existence until about 1912. Sometime before that Eugene Morenus had withdrawn from his position and was succeeded by John Kime. Mr. Morenus and his brother, Granville Morenus, had established glass factories in Pennsylvania near supplies of cheaper fuel. This was natural gas, which gave a steady heat and was less costly than wood. Four or five glass houses had formed a combination to market their product. Then the Sherman act was passed and to operate this group of factories as they had been doing it was feared would be held illegal. Tf the law was upheld the heads of these houses would be subject to fines from five to ten thousand dollars and five to ten years imprisonment. They were afraid to proceed and after storing large quantities of window glass in their warehouses, they closed down their factories which never reopened. Shortly after the closing of the factories the Sherman act was interpreted to be applicable only to large enterprises and their business could have been continued legally. The stores of glass were sold at a great sacrifice to what the Cleveland’s bitterly called “the Jews”—who were supposed to have made large sums out of the transaction.

Bernhard’s Bay, on the lake a little to the west of Cleveland, also had a glass factory established in 1847 by Ferris Powell and Israel Titus.

In 1863 after sixteen years of successful operation, this factory was sold to a group of investors and carried on under the firm name of Stephen & Crandell & Co. The incorporators of this organization were Dewitt C. Stephens, K. Martin Crandell, Clinton Stephens and Frank Willard Bennett. Later Mr. Crandell was succeeded by his son, Elmore Rockwood, and Mr. Stephens by his son, Albert, and Richard Douglas was admitted to the partnership. In 1873 the firm was doing business under the name of Bennett & Beckley. Ten years later Clark Hurd & Co. succeeded them and in the middle eighties. Potter & Marsden were the operators. But the business declined, laborers left their jobs to go elsewhere, and on July 5, 1895 the factory burned and was never rebuilt.

Miss Sophiei Crandell, the granddaughter of Stephen, is living in Bernhard’s Bay and has given me an interesting schedule of the working hours of the blowers for the pot furnaces.

From midnight Sunday until 11 Monday; from 7 a. m. Tuesday until 6 p. m.; from 1 p. m. Wednesday until 12 p. m.; from 12 noon Thursday until 11 p. m.; from 7 a. m. Friday until 6 p. m; from 7 a. m. Saturday until 6 p. M.

With an hour out for lunch this made a sixty-hour week.

On Wednesday evening visitors were admitted, and as a concession to Victorian modesty, during that period the blowers were requested not to remove their shirts while working.

Glass Blowers at Mexico

In recent years there has been living in Mexico a family of glass blowers. These people are descendants of Charles Marrithan, a glass blower of Alsace, France where he was employed by the Baccarat Glass Company in making flowers for paperweights. He was the only member of his family who knew the secret of mixing colors and never was allowed to tell his son. His son Charles and his wife, both Alsace born, came to New York after their marriage and worked in factories near Boston and New York. The third Charles was born in New York and due to ill health was sent to Colos-se to live with an uncle. He, his wife and daughter worked together for many years and travelled through the country showing their craft at country fairs and expositions even as early as the centennial in 1876. His last years were spent in Mexico where he blew fragile bits of glass from material which he obtained at Corning. Members of his family are still carrying on with their work.

Cleveland Birthplace of First American Labor Union

Mr. William Gallagher — your county attorney—is the son of Mr. James Gallagher whose advice and plans enabled this Cleveland glass works to operate for its last period.

He recalls many interesting incidents of the glass days of Cleveland. What seems of unusual interest is that Cleveland is the birthplace of unionism in the United States.

Frank Putney, a veteran of the Civil war was secretary of the Cleveland Glass Company. He evolved the scheme of a secret organization of workers.

It was then against the law for workers to organize but they did at Cleveland, and seemed to have controlled firing and hiring and wages by secret methods. They held their meetings outdoors in a nearby ravine, where they were completely hidden from observation.

Mr. Samuel Gompers, who was then a young cigar worker, learned of the scheme and spent some days visiting Frank Putney in Cleveland and secured complete information as to the organization and methods of the glass workers union. He returned to New York and organized the Cigar Workers Union —his first. Later Mr. Gompers was head of the American Federation of Labor for many years.

This is Mr. Gallagher’s story. I am mentioning it briefly. I hope that some day he himself will tell the members of the Historical Society about it.