This essay was originally published in the 1942 OCHS Yearbook. Please note that this essay was published over 82 years ago. While still useful for general education, language may be outdated and at times offensive. The Oswego County Historical Society does not stand by the language used in this essay. All photos were added in 2024 when this article was uploaded to the web. To view the original document, please visit NYHeritage.org.

Paper Given Before Oswego County Historical Society at Oswego, March 10, 1942, by Dr. Lida S. Penfleld, Former Head of the English Department of Oswego State Teachers College

At the time of the recent World’s Fair in New York City, each county of the state was asked to contribute an account of artists native to the area Commander John M. Gill prepared an excellent report on the writers of Oswego County which was printed in the “Post Standard.” If the war had not summoned Commander Gill to service, he would have been the one to record for the Oswego Historical Society at greater length, the life and work of Morgan Robertson in the series of papers planned by this society to give honor to the writers and other artists of Oswego.

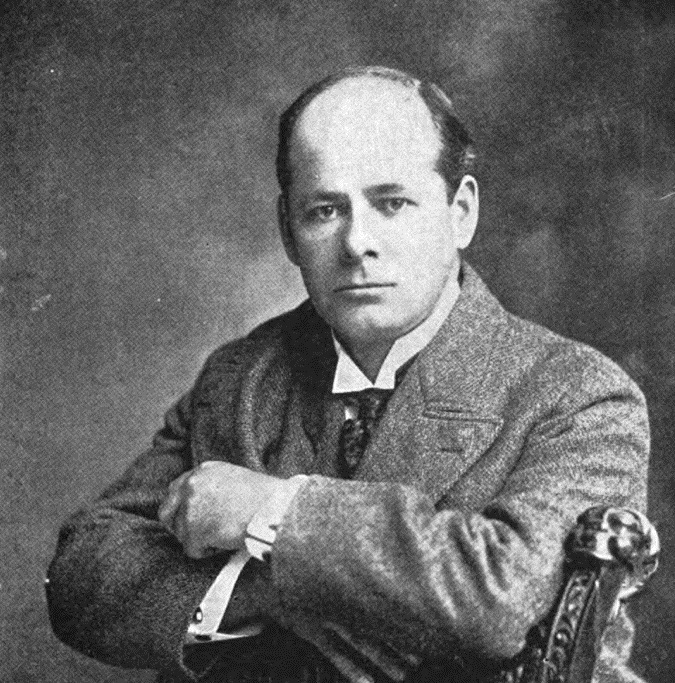

“Gathering No Moss,” published in the Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1914, is the title Morgan Robertson gave to the story which he wrote of his own life. Full of ups and downs and roundabouts, that life ranged from sailing the Great Lakes, circumnavigating the globe, cow punching in Texas, learning the gold smith’s art, diamond setting, and clock repairing, through the disheartening and valiant struggle to earn a living, hand to mouth, in New York City, through threatened blindness and nervous breakdown Always on the move, never completely bogged down, forever dabbling and experimenting — small wonder that he thought of himself as a rolling stone. As for moss, what had he accumulated ? Certainly, little money, few possessions, no establishment, but friends, yes, many of them, maybe even a few enemies, for good measure, and a rich treasure of experience.

His Books Made Him Friends

His books made friends for him. Those stories of the sea, so vigorous, so salty with humour[sic], so direct in action, so skilled in seamanship, found favor with those who enjoy a well spun yarn, whether they go down to the sea in ships, or stay ashore.

Charles Lee Lewis, instructor at Annapolis Naval Academy, writing about Mc gan Robertson in the Dictionary of American Biography (vol. xvi. p. 27), thus catalogs the stories:

“His stories deal with sailing ships, steam vessels and the long steel men of war. They treat of mutiny[sic] and bloody fights, ship wreck and rescue, brutality, shanghaiing, courage and wild daring, telepathy, hypnotism, dual personality, and extraordinary inventions.”

Booth Tarkington, in McClure’s Magazine (October, 1915, p. 90), wrote: “His stories are bully, his sea foamy, and his men have hair on their chests.” Joseph Conrad wrote to Robertson:

“Indeed, my dear sir, you are a first rate seaman—one can see that with half an eye.”

Stories Surprised Oswego Friends

In the earlier years, his success with his stories was a surprise to his friends in Oswego. Nothing about him was bookish. Of medium height, broad shouldered, stockily built, of dark complexion, with a “rough” voice, he is better remembered here as a sailor than as a writer. In company, sometimes, he would be lost in a brown study, and then break his silence with [sic] voicing a novel idea or a practical joke. He usually wore the square cut marine reefer jacket. From five dollar gold pieces he fashioned buttons for his coat and appeared one autumn in Oswego all a glitter[sic], to the astonishment, especially of the young ladies. As the winter of his stay lengthened, the buttons gradually disappeared from the jacket, returned, it was surmised, to circulation by the owner.

His Uncle Dubbed Him a “Fool”

One winter, between voyages, he settled down to learn the jew eler’s business with a Mr. Barnes, who had a jewelry store on West First street, about where Thomas F. Hennessey now has his drug store. He made his home with his uncle, Mr. Moses P. Neal. Wishing to express his appreciation for that hospitality, he insisted upon installing cathedral chimes, a complete set of them, in the clock that stood on the shelf in the Neal sitting room. So loud and so long were the hour changes rung by the resonant chimes that the exasperated uncle thus vented his wrath: “I always thought he was a fool, and now he has made himself a monument for it with that clock.”

Apparently Morgan didn’t particularly mind being called a fool, but he was ready for the man who called him (as some were occasional ; tempted to call him) crazy. “Crazy am I ?[sic]crazy?” “What’ll you bet that I can’t prove that I am sane and not crazy?” With the wager made, Morgan would triumphantly produce his legal discharge from Bellevue Hospital as the document in evidence and laughingly gather up the stakes.

Everyone who knew[sic] him seems to cherish a good story about him, as a sailor, as an original, as a master hand and unique[sic].

An obituary not always gives a true picture of a man, but the tribute that appeared in the “Oswego Palladium,” March 25, 1915, the day following Robertson’s death is so sincere, from the nick name of his boyhood, “Morg”[sic] to the last picturesque detail of his cabin in a studio, that we know it was written by the hand of a friend. The Palladium obituary notice follows:

“MORG. ROBERTSON DIES SUDDENLY”

“End Came at Atlantic City Yesterday Afternoon.

“Famous Writer of Sea Stories, an Oswego Boy, Passed Away Standing Up in His Room at a Hotel—Born in This City in 1861”

“ATLANTIC CITY, N. J., March 25—Morgan Robertson, the author, was found dead in his hotel room here yesterday afternoon. A half filled bottle of paraldehyde, a sedative, was found on his [sic]bureau. County Physician Leonard said, however, that this medicine had nothing to do with his death, which was caused by heart trouble.

“Mr. Robertson came here a few days ago suffering from a nervous collapse. He spent most of his time on the beach and on the boardwalk. The change of air was apparently having a good effect upon him.

“He went to his room shortly before noon to lie down and asked that a bellboy call him in time for luncheon.

“A rap at his door at one o’clock failed to bring a response. The boy opened the door and found him leaning lifeless across the bureau.

“Mr. Robertson was born in this city on September 30, 1861, and was the son of the late Captain Andrew Robertson and Ruth Glassford[sic], the former a well known master of lake going vessels. Back in the seventies, when a boy in his teens, ‘Morg.'[sic] Robertson knew every stitch of canvas and line on the fore and aft canallers and barkentines that made Oswego a port of call. He had made frequent trips with his father on the lakes during the long summer vacation days and could steer his trick with the best of the men when the weather wasn’t too heavy. But he yearned for greater experience and when Captain Davis, sailing a clipper ship out of Boston in the China trade, offered him a passage as a cabin boy he accepted gladly and sailed away into China trade. He was then sixteen year.i old. It was several years before he came back. He developed a dislike for Captain Davis who he found was not like the free and easy skippers of the lakes, whom he knew and who had made much of him because he was Captain Andy’s boy.

Wearied of Sailor’s Life

“During his sailing days on salt water he picked up navigation, made many ports active in the world’s commerce, was shipwrecked and had many adventures. When he returned he was a full fledged sailorman, but the life to him had become distasteful. All of the glamour had been expelled by his personal contact and experience and he frequently said to acquaintances that he was through with the seas. However, there was no man who had a better knowledge of ships or sailing and the accurate knowledge he had picked up made his stories of deep sea life all the more interesting and claimed the attention of those who recognized them as the true reflection of a writer who was fully acquainted with his subject.

“While afloat Mr. Robertson became an adept[sic] as a worker in gold. He made handsome watch chains with anchors and snatch blocks, through which ran the finest of gold wrought chains. Some of those are still extant among his old friends in this city. When he decided to quit sailing he went to New York expecting to be able to get a position in one of the large jewelry manufacturing concerns, but there was nothing doing in that’ line.[sic] One day he read an advertisement of Tiffany[sic] that he wanted diamond setters. Mr. Robertson had never set a diamond in his life, but he thought he could get away with the job so he applied and got the place. The superintendent quickly saw that he had never set diamonds and told him so. Mr. Robertson admitted that it was his first experience and said that the reason he applied was that he must get a place to work. The superintendent liked his talk and appearance and Mr. Robertson was continued[sic] in a position setting other stones and eventually became one of Tiffany’s most expert diamond setters, thus obtaining a knowledge of diamonds possessed by few. He continued in the vocation until 1894, when his sight failed

Inspiration Came From Kipling Story

“In 1896 while he was in New York a friend handed him one of Rudyard Kipling’s sea stories and told him to read it. He did and that night he began and finished his first short story, writing on a washtub until dawn. He called it ‘The Destruction of the Unfit.’ He submitted it to a newspaper syndicate, where it was refused because of its length. It was then sent to a magazine and after a long delay was accepted for $25. During the year that followed Mr. Robertson wrote and sold about twenty short stories of the sea. Since then not a year and perhaps not a month passed in which one or more of his sea pieces did not appear.

“His first book was ‘A Tale of a Halo.’ It was a good seller and then a suggestion was made to him that he specialize in sea stories. He did and while he never proved a Clark Russell, he wrote many interesting stories, of which the following were some of the best ‘Where Angels Fear to Tread,’ published first in Atlantic Monthly; ‘Salvage’ in the Century; ‘The Brain of the Battleship’, ‘The Wigwag Message’, ‘Between the Millstones’, ‘The Battle of the Monsters’, all in Saturday Evening Post; ‘The Trade Wind’, Collier’s; ‘From the Royal Yard Down’, Ainslee’s: ‘Needs Must When the Devil Drives’ and ‘When Greek Meets Greek’, McClure’s; ‘Primordial’, Harper’s. “

‘The Wreck of the Titan.’ written about a year before the sinking of the steamer Titanic, was regarded after the accident as almost a prophecy; telling how such an accident were[sic] possible by collision with an iceberg, and it was reprinted in many magazine editions of Sunday newspapers.

“A few months ago Mr. Robertson’s last story was published. It told of the fate of the writer of sea stories when he became written out. After that friends took his affairs in charge and an edition deluxe[sic] of his stories was printed and had a large sale. Several magazines have given them as premiums.

“It was several years since Mr. Robertson visited Oswego and few of his friends here are acquainted with his latter day affairs. He was married in 1894 to Alice M. Doyle, of New York, and their home had been at 140 West Thirty fifth street. His only brother, William Robertson, is connected with the operating department of the Nickel Plate Railroad, with headquarters in Cleveland, and a sister, Mrs. Alice Sheldon, lives in Ashtabula or Cleveland. Mrs. Morgan Wheeler, of West Fifth street, was Mr[sic] Robertson’s aunt and Mrs. E. B. Mott is his cousin. Friends here have not yet been told of the funeral arrangements.

Invented a Periscope

“Besides his being a sailor, a diamond setter and an author, Mr. Robertson was an inventor, having devised in 1905 an improved periscope for submarines which was bought by the Holland Torpedo Boat Company. This invention grew out of an imaginary instrument used for the embellishment of a submarine story.

“Robertson’s studio in New York was fitted like a ship’s cabin, with all the comforts of sleeping room[sic], diningroom[sic], kitchen, bathroom, library and den. On one side of a draped couch he had a cushioned window seat, under a porthole. His bathtub could be covered and used as a table. In one corner was a gas range on which he could make coffee and other light repasts when immersed in his work. The room was papered with illustrations of his stories.”

Author’s Edition of Eight Volumes

The published volumes of Robertson’s stories include: “A Tale of a Halo” (1894); “Spun Yarn” (1898); “Futility” (1898): “Where Angels Fear to Tread” (1899); “Masters of Men” (1901); “Sinful Peck” (1903); “Down to the Sea” (1905); “Land Ho!” (1905); “Chivalry,” a play (1913).

In 1914 an author’s edition gathered into a uniform edition, the tales Mr. Robertson selected for his complete edition, comprising eight volumes. The titles were in part a repetition of those borne by earlier printings of single volumes. In all there were included two long tales, “Masters of Men” and “Sinful Peck,” each allotted a volume. In the remaining six volumes there were sixty three of the more than two hundred stories he is said to have written. In this edition the titles were”The Wreck of the Titan or Futility,” “Where Angels Fear to Tread,” “Down to the Sea,” “Three Laws and the Golden Rule”, in which were included four of the stories from “Spun Yarn”, “The Grain Ship”, “Over the Border”,, “Sinful Peck” and “Masters of Men.”

Story of “Masters of Men”

“Masters of Men” is dedicated, “To my wife, a good woman.” It is the story of Dick Halpin, a red haired and freckled orphan lad, who joins the navy, a few years before the Spanish American war. The boy goes through the rigorous training on ship board, rising step by step to be signal man.[sic] By reason of Dick’s gallant service in action at the blockade of Santiago, he wins a commission. Bronson, Halpin’s sponsor and himself in service, gives the keynote of the story; “It’s a tough life, and makes a machine of a fellow.” A hilarious section of the story tells how young Halpin brings home’ with him a dozen shipmates to help him pay back a grudge against a group of hateful school mates. As the fight mounts to a climax, the citizens bring out the fire department to drown the fracas. “Masters of Men” was made into a movie. It was played in Oswego at the Orpheum theater. Mr. Charles P. Gilmore, who managed that theater, remembers the picture but cannot supply the date of its showing.

“Sinful Peck,” the second full length tale, is built around a practical joke played as the result of an election bet when Bryan ran for President. Peck, the loser, must ship for a year as sailor, or forfeit $10,000 to Seldom Helward. A group of old shipmates, now successful men of Cleveland, Ohio, go to New York to give “Sinful” a fitting send off. At the dinner given the night before “Sinful” is to sail, he drugs the other guests and has them, unconscious as they are, shanghaied to his ship The adventures that follow run the gamut of stirring mutiny, pirates, storms, rescues, hairbreath[sic] escapes, and fights aplenty.

Oswego Sailors As Characters

“Sinful Peck” and his friends first appeared in the short story. “Where Angels Fear to Tread,” one of Robertson’s early tales, and especially interesting to us because the lively group of lake or “fresh water” sailors who sign up with a merchant ship, the “Almena,” a square rigger, of course, outward bound, round the Horn for Callao, are all from Oswego, N. Y. They are all “weill[sic] fed, well paid, self respecting citizens “who sign up using their nicknames. These nicknames are authentic. The late John S. Par sons of Oswego knew the real names of the men who answered to them on the lakefront. Here they are as Morgan Robertson fitted made up names to the nicknames: Tosser Galvin, Senator Sands, Turkey Twain, Big Pig Monahan, Jump Black, Gunner Meagher, Moccasey Bill, Yam paw Gallagher, Ghost O’Brien, Sinful Peck, Sorry Welch, Poop deck Cahill, Seldom Helward, Yorker Jimson, Shiner O’Toole, General Lannigan. The fun of the story is that sailors on the Great Lakes are better men than salt water sailors. They are used to better treatment. Their awakening to the realities of seafaring is startling. These Oswego men “would[sic] rather fight than eat.” There is a fort at Oswego (the story dates back to the early 1880’s), and whenever a company of soldiers becomes unmanageable, the War Department transfers them to Oswego—and they are well behaved, well licked soldiers when the ‘ leave. “An Oswego sailor loves a row.” How these Oswego sailors get the upper hand and escape, even from the police in New York harbor, makes lively reading.

Pirate Stories in One Group

One of the figures invented is the lovable old Finnegan, on the battleship Argyll. In Robertson’s stories the kindly rascal is like Mulvaney, the soldier in Kipling’s stories. He appears in “The Brain of the Battleship”[sic] and several other tales.

Another group of stories deals with a pirate ship, Captain Swarth and Angel Todd, the first mate.

One of the physicians in Oswego, I am told, thinks the finest story Robertson wrote is “The Battle of the Monsters” because of its imaginative and original presentation, in a day (1888 1900) when the facts were known to few outside the laboratory, of the struggle in the blood stream of germs—the germs of hydrophobia and cholera are conquered by the leucocytes[sic], showing that Robertson dramatized Metchnikoff’s theory, based on microscopic examination of blood, of fighting leucocytes[sic].

To another reader—a businessman, there is the greatest thrill in “The Closing of the Circuit,’ included in the volume “Down to the Sea.” This is the story of a boy, born blind, brought up in ignorance of his lack of sight. How he runs away to sea and regains his sight by shock is the action. The thrill lies in the vivid realism of the scene where the boy gradually is aware of the miracles of vision.

Many a man owes an hour of relaxation to the magic of the forthright, manly, sea stories of Morgan Robertson.

In preparing this study I have been helped by many. Old friends of Morgan Robertson have shared their personal knowledge of him. Mr. Fred P. Wright gave me the use of his filed[sic] material about Morgan Robertson. Mrs. Caroline Hahner[sic] at the State Normal School and Miss Forward at the City Library have given me valued aid.