“This essay was originally published in the 1941 OCHS Yearbook. Please note that this essay was published over 83 years ago. While still useful for general education, language may be outdated and at times offensive. The Oswego County Historical Society does not stand by the language used in this essay. All photos were added in 2024 when this article was uploaded to the web. To view the original document, please visit NYHeritage.org.”

(Paper Read Before Oswego Historical Society at Oswego, February 18, 1941, by Robert Macdonald, Principal of Fulton High School)

Spring 1756: Marie[sic] Theresa of Austria had at last persuaded the French and Russians to espouse her cause against Frederick of Prussia. England in alarm sided with Frederick and the Seven Year War, the war to decide which should be the leading nation in the world, France or England, was on. During the two years previous, French and English colonials with some help from the mother countries had been at war. Fortune, abetted by English stupidity and colonial jealousies, had favored the French until the English colonies were hemmed in between the Appalachian Mountains and the sea. The St. Lawrence Valley, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio Valley were firmly in French possession—with one exception— Oswego. The only break in the mountains through which easy access might be had to the west was up the Mohawk and down the Oswego Rivers. Because of this and because of the menace it gave to the French lines of communications, Oswego was fortified and a garrison of 3000 troops placed there in the summer and autumn of 1755. Plans were made to build ships at Oswego to carry the war to the French on Lake Ontario. Here our story begins.

Early in 1756, John Irving, Jr., of Boston, probably a contractor, approached Philip Coombs of Newbury, Mass., with a proposition to obtain ship carpenters to go to Oswego to build ships for the King’s service. He was successful. On March 1, Philip Coombs with seventeen others signed an agreement with John Irving. Among those signing this agreement was Stephen Cross, 24 year old nephew of Philip Coombs. A week later, the party set out for Boston, arriving [sic]next day. The following day was spent in obtaining supplies and tools. Early the next morning, having been joined by nine men from Boston, the carpenters set out for Providence, forty five miles distant. We don’t know what conveyance they used— maybe they walked—anyway it took them two days to make the journey. A small sloop was waiting for them in Providence which they boarded at once and set sail at one o’clock, March 12.

Nine Days On Hudson

We’ll pass over the trip to New York. In such a ship, a trip to New York in the middle of March down Narragansett Bay, around Point Judith and the full length of Long Island Sound must have been something short of pleasurable. Stephen Cross tells us that the master of the ship didn’t want the men to go ashore at Newport for fear they would desert. The event proved his fears were groundless, but it is surprising that some of them didn’t sicken of their bargain, and take “French leave.” The party arrived intact in New York shortly after midnight, March 17th. In the morning, they “went on shore and viewed the City”. Noon saw them embarking on another sloop, setting sail for Albany at sun down. Nine days later, “after a verry[sic] dull voyage” they arrived in Albany. Here they took their things ashore and lodged in a tavern kept by one Sotnidges. To this point we have traveled with the party. From this point on let us keep close to the side of Stephen Cross.

The rest of Friday, the 26th, was spent in “viewing the city.” Saturday, baggage and tools were loaded into a wagon and the little band walked to “Scenactadi”[sic]. (Even at this early date, Schenectady was a spelling demon). Stephen found “this little town Situate[sic] on the Bank of the Mohawk River exceedingly thronged with Soldiers, Battoe[sic] Men, and Workmen Building Battoes”[sic]. This was the take off place for all travel west. All was [sic]hustle and bustle. Housing accommodations Were taxed beyond the limit. Some of Stephen’s party[sic] were put in a cooper’s shop. Stephen himself, [sic]was more lucky. A half mile up the river he found lodgings at which he was very hospitably and well entertained. Stephen was well brought up. The next day, Sunday, he attended divine services at which a chaplain of one of the regiments “offisiated”[sic].

Alarming News From Rome

No time was lost in putting the new carpenters to work on building the batteau. For the next week the men worked their hands at their craft and their ears and tongues on rumors and criticisms. One day the news came that the enemy had attacked one of the forts at the Great Carrying Place (Rome) and had taken it. Then the word passed around that next day the work men were to be sent to Oswego with 600 men. Stephen didn’t like this one. He says “How Disagreeable the Prospect when the enemy was reducing the forts on the way”. Can we blame him? Then more news of the fight at the Great Carrying Place. General (Sir William) Johnson had gone to the relief r,l the second fort which was being invested. The 600 men mentioned above were sent on to the general. Of these 600 men, 170 were recruits with neither arms nor ammunition Stephen says: “It Appeared Strange to us to See men Sent tomorrow, when we knew the Enemy were in the way, without arms”. Strange, indeed, then! See the account of the British fiasco in Norway in the spring of 1940.

Later reports from the Great Carrying Place said that Lieut. Hull and 60 men were killed or captured and the fort on the further side burned. General John son chased the attackers but could not overtake them. On Sunday April 4th Stephen “attended worship where a Common Soldier by the name of Wil liamson preached. I believe a good man made many Good observations and good admonitions and councills”. Apparently Wil liamson made more of an impression on Stephen than did the regimental chaplain on the previous Sunday. From Schenectady To Rome In 18 Days Toward evening on the follow[sic] day two companies of soldiers and the carpenters started up the Mohawk for the Great Carrying Place about 100 miles away. The trip which today is nothing more than a comfortable morning’s drive took this party eighteen days. Some days, as on April 6th, they proceeded as little as four miles. The company was not wholly to Stephen’s liking because two of his friends had personal belongings filched from them. “We found our Selves[sic] in very Disagreeable Company”, he says. At one of the Indian Castles he heard Abra ham, brother of King Hendrick make a speech to the Mohawks who were to accompany the expedition. Some damage was done to the boats in making the —8— portage at the Little Carrying Place (Little Falls). Colonel Bradstreet ordered the carpenters to repair the boats. This occupied them the better part of two days. On April 23rd they arrived at the Great Carrying Place.

Misery must have been the lot of the men for the next three days because Stephen reports nothing but the weather on the 24th, 25th, and 26th, rain, snow, squalls, and cold. On this last date, “our Carpenters Company agreed to take charge of the 20 whailboats[sic] which Capt. Williams and his Company had Brot[sic] up”.

The next eleven days were busy ones. One day the carpenters were sent to the west side of the carry to cut trees to build a new fort to replace the one the French had burnt. A close survey of the east and west side of the “carry” showed that Wood’s Creek made a turn. Some pioneer troops were detailed to clear the fallen trees and tag alders from the upper part of the creek. Clearing this part of the creek would shorten the “carry” from four miles to one mile. It becomes evident here from Stephen’s account that the carpenters were not subject to direct military command. “Coll. Bradstreet Proposed to us to joyn[sic] this Company of Pioneers and assist them in this Business for which he promised us half extra wages”. Thus early the bonus for special work! The Carpenters agreed to the proposal. Working up the creek from below, they met the pioneers working down from above, on the night of April 29th.

Hurry To Relieve Oswego Garrison

Haste at the “carry” was imperative. Earlier in the spring a drove of cattle had been sent to Oswego to relieve the great shortage of food for the garrison which had been evident even before winter set in. It was believed by the men in Stephen’s party that the soldiers at Oswego were in great distress. Doubt was expressed that the cattle reached Oswego because the French and hostile Indians were roaming at will about the country and had probably intercepted the drovers. Speedy succor[sic] for the garrison was a pressing necessity. On April 29, however, the drovers returned from Oswego. They had been successful in getting the cattle to Oswego except as Stephen says “a fiew[sic] which our good friends Indians took from them”. The drovers also reported that the garrison was very sickly.

Fear of the French and Indians was ever present. Two nights in succession the alarm was given. All soldiers were kept under arms throughout the night but no attack was made and search in the surrounding woods the next morning failed to give any evidence that any enemy had been near the encampment during the night. One day three Oneidas, supposedly friendly, were brought in and questioned. They claimed that they had been captured by a small party of French and Indians and held prisoners for a day and a half. On releasing them the hostile party said that they were going down the Mohawk to capture a family but that they would soon be back. “By this,” Stephen says, “we Suspected our Indians were not to be depended upon for defence[sic]”.

From May 2 through the 7th, chilled by the cold rain, the party struggled through the mire a thousand times worse by the constant churning by men straining every muscle to push the boats over the “carry” on rude rollers. After the boats had been launched in Wood’s Creek, all of the baggage had to be packed over the “carry”. Stephen doesn’t complain about the hardships, but the very terseness of the account permits the reader to fill in the gaps to complete a picture of misery.

On May 8th the party proceeded down the creek with great difficulty. The water was low; the whale boats of the carpenters were at the end of the line; the creek was very narrow and obstructed by fallen trees. Everyone was so impatient to get ahead that the boats often fouled each other and locked. One can imagine the amount of lurid language that was loosed[sic] upon the air as the men struggled to disengage their boats. Once the tie ups was[sic] so complete that Stephen’s party quit and camped in the woods for the night Three days were consumed in moving the fleet of 500 batteaux and whaleboats from the Carrying Place to Oneida Lake. A real relief it must have been to come out of the creek into the lake. April 5th to May 11th, six days over a full month had been consumed in going from Schenectady to the head of Oneida Lake.

Stephen estimated that Oneida Lake was 20 miles wide and 30 miles long—not a bad guess though a little overestimated as we now know the lake. It may be that at that time the lake was somewhat larger than it is now.

Spend[sic] Night at Frenchman’s Island

Between noon and dusk the fleet went twenty miles down the lake. Once two Indians were discovered on a point of land. Supposing them to be hostile, a party was sent shore[sic] to try to capture them but their attempt was unsuccessful. The night of May 11th, was spent on an island probably the one we now know as “Frenchman’s Island,” located between the Syracuse Yacht club and Constantia.

May 12th was a pleasant day. A slight breeze was blowing from the east so that anything that could possibly serve was set up for a sail. When all of the fleet of 500 boats was under way the whole end of the lake seemed to be alive. Stephen says “a more agreeable Sight I Scarce ever Saw”. The boats raced along for ten miles each striving to out do the others. A surprise was in store for the fleet at the entrance to the Oswego River. A band of friendly Indians set off a volley of musket shots by way of welcome. The fleet was thrown into confusion because it was believed an attack was being made. The mistake was soon discovered and no damage was done. The boats entered the river (Brewerton) and, driven by a fair wind and strong current, soon came “to the Three Rivers —so called”, Stephen says, “being the Junction of the Onadga River with the Main River”. Now, of course, there are three rivers by name, the Oneida and Seneca uniting to form the Oswego at Three Rivers. Stephen’s spelling of the name of the river from the west may have been through an unintentional omission of an “a” between the “d” and the “g”. Later in the diary he spells it Anadagga. If my memory serves me, at an early date, the spelling of Onondaga was substantially the same as it is today. When the name of the river was changed from Onondaga to Oneida, I am unable to say.

Boatmen Drenched Near Phoenix

A short stop was made at Three Rivers to allow the rest of the flotilla to come up, for the boats had become separated in the trip down the Oneida River. After they had assembled, the trip down the[sic] Oswego was begun[sic]. At or near the location we now know as Phoenix, they unexpectedly found themselves at the brink of a considerable falls[sic]. No warning had been given so the only thing they could do was to run the falls as best they might. Stephen and his party were lucky in having no mishaps but a number of boats in the flotilla capsized and others filled with water, but no lives were lost. The ducking the men received was inconsequential. In the course of the night the boats arrived at an island where the whole company camped for the night.

As one comes north on the East River road of today just south of Fulton, the first sight of the river shows an island now called Big Island. It was on that island, then much larger than it is today, that the company camped for the night on May 12, 1756.

The First Casualties

The next day was spent in reconnaissance and making preparations to pass the falls of the Oswego. It was fully expected that the enemy would be at the falls in force to prevent the expedition reaching Oswego. Inasmuch as no real attempt was made at the Great Carrying Place, it was logical to suppose an attempt would be made here because here was the last place that any serious disorganization in transport might take place. A number of men were landed on the east bank of the river to search the woods. Another party was assigned the task of taking some of the boats to the head of the falls. (These falls were just above the upper bridge in Fulton between the Sealright[sic] and American Woolen Company plants, approximately where the upper dam is now located.) No signs of the enemy were discovered, a very agreeable surprise. The contingents to which Stephen was assigned, hauled one whaleboat out of the river, cut some skids, and dragged it around the steep part of the falls, a distance he says of a few rods. Just where this particular “carry” was we cannot say. Later, the “carry” was from a point just above the Sealright[sic] property to a point between the present sites of post office[sic] and the library.

Below the steep part of the falls was a mile of rough water filled with dangerous rocks. Anxious to get news to Oswego that the expedition was on the river, the whaleboat was launched just below the falls and a crew of three men assigned to run the rapids with it. Bad luck was their lot for it struck a rock and was stove in. Two of the crew were rescued; the third drowned. Stephen thought they were lucky to save two men “which was more than we could expect.” The party returned to the main body at the island for the night.

Attempt to Run the Falls

May 14 was a memorable day and Stephen described the happenings of that day in greater detail than he does any other day of the trip. Early in the morning the whole party moved to the head of the falls. Here the boats were hauled out of the river, dragged along the carry, and launched to run the rapids. The carpenters did not choose to ride the rapids because it was so dangerous. They carried their tools and baggage below the rapids to a point possibly near the Logan Long Company’s plant, where they were taken on board. Several men lost their lives and many boats were wrecked in running[sic] the rapids. In any large body of men there are boasters who can tell those who command how to conduct their affairs. In this expedition was one, not named, who was sure too much time was being lost in hauling the boats around the falls. He said for a small sum he would run the falls. Col. Bradstreet agreed to his terms. He obtained a crew of three and took a boat over the falls. The task was too much for him. The boat filled with water. The pilot was thrown clear of the boat toward the east bank where he was rescued. The others clung to the boat. Two were finally thrown out and drowned. The fourth was lucky enough to hang on through it all and was rescued below the rapids. After embarking, Stephen’s party went down the river about three miles where they took on a pilot to take them over a bad reef below. The contour of the river has been changed so much by the dams and the building of the canal that it is impossible today to state exactly where this reef was. It is possible that it lay between the Arrowhead Mill and Battle Island or it may have been near the River View Park. The party arrived safely in Oswego at 5 p. m.

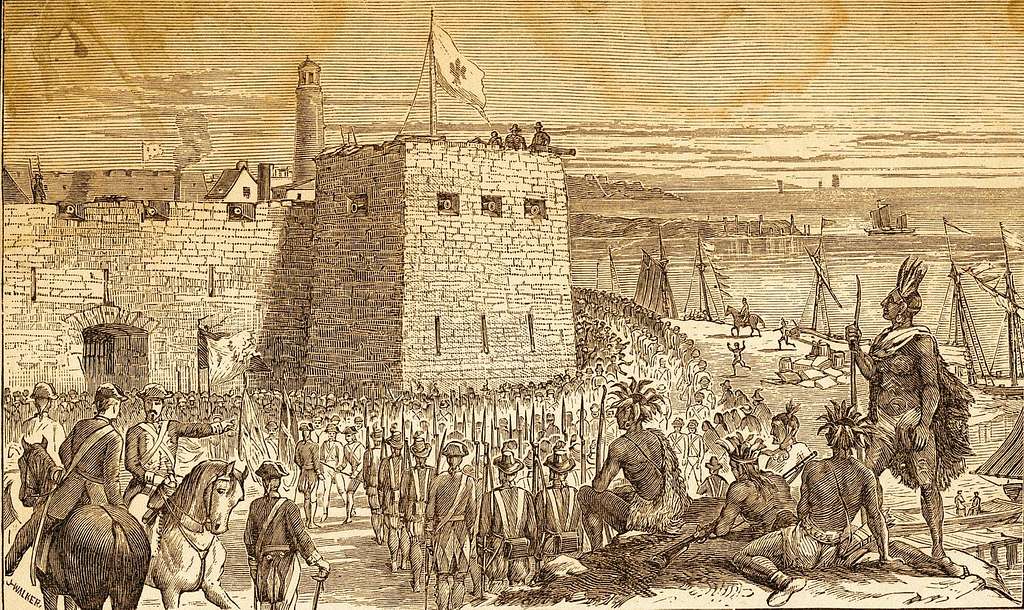

The Vista at Oswego in 1756

Here I will give an extended quotation from the diary: “On our first coming in sight of the fort after having been so long and come so far and seen Nothing but Dreary Uninhabited Woods, all at once to open up as it were a Seaper . (?) so the Lake Appeared, and on one side of the River on a high Steep Bank see a high Stockade fort, and the Ramparts lined with men, on the other side a high Promontory like, with a stone fort on it, and on the landside fortified with a Foshene (fascine)[sic]Batery[sic], and a number of cannon mounted with the British flag on top of the Stone Fort and a number of Small Traders and Settlers Houses and a Hospital on a line on the bank of the River, above the fort, and in the Harbour, Vessels, lying with their Colors Displayed. I say this sight was Exceeding Butiful[sic] and Grand which gave a Spring to our Spirits”.

The men in the expedition were not the only ones happy that they arrived. The soldiers at the fort were “in an extacy[sic] of joy”, to receive the supplies that had come. All winter and spring they had been on extremely short rations. “Only one pint of Flower, put Litely in, and half a Pound of Pork a day.” Many were sick and all were in low spirits.

The carpenters began work the next morning. They cut timber out of which they sawed boards from which they built their barracks. From subsequent entries it would appear that these barracks were built near the Fort[sic] Oswego on the west side of the river. From the maps of that time of the harbor, Fort Oswego must have stood near the foot of West Van Buren street.

Deadly Peril Lurked In Woods

From the first day the carpenters arrived it was evident that the fort was being very closely watched by the French, and their Indian allies. On May 15 some friendly Indians brought in a Frenchman’s scalp. On May 17th 23 men sent from the fort as a guard to The reef were attacked. The officer in command and one man was killed Nearly every day from then on, Stephen records seeing Indians or reports attacks beine[sic] made on any men who strayed away from the immediate vicinity of the fort. Apparently the English were entirely hemmed in with little or no knowledge of what was being prepared for them by the French. On the 25th of May Stephen wrote “this morning found the Indians had killed 3 Dutch Bat toe Men, who had camped about a Stones through (sic) from the hospital, having come upon them asleep, and cut their throats ana scalped them before they fired off a gun. One of our soldiers came in from the edge of the woods Where it seems he had lain all night having been out on the evening party the day before and got drunk and could not get in and not being missed, but on seeing him found he had lost his scalp, but he could not tell how nor when, having no other around. We supposed the Indians had stumbled over him in the dark, and supposed him dead, had taken off his scalp.”

The work for which the. carpenters were engaged went[sic] forward. The shipyard was near Fort Oswego. The vessels which Were already in commission were repaired. Two new vessels wert started, a brig and a snow, the latter a square rigged vessel” with a trysail mast abaft the main mast[sic]. On these vessels work was pushed as rapidly as possible that they might be ready when the army arrived.

Danger Of Siege Impends[sic]

On May 31st four Indians came into the fort with the information that 1500 French and Indians had come over the lake. We know that the French began to gather in force (under DeVilliers) near Henderson Harbor and that the force of 700 that attacked Col. Bradstreet at Battle Island early the following month came from this encampment.

Ships were constantly sent out from Oswego up and down the lake to get information. From what Stephen tells us this information was meagre[sic]. There were French ships on the lake that were more heavily armed than the British vessels and on occasion chased the British vessels almost to the guns of Fort Ontario.

Every few days small parties arrived from Schenectady with batteaux of supplies. Apparently the French were not particularly concerned with stopping the flow of supplies into Oswego. They were waiting for the goose to fatten before making the kill. On June 16th a general alarm was given that the enemy was preparing to attack in force. A lively skirmish took place. Indians crossed the river above the fort out of cannon shot, possibly near the site of the later Kingsford Starch Factory. Many shots were fired from the cannon of both main forts at Oswego. After a three quarters of an hour of brisk fighting the Indians withdrew. The English now began to think seriously of being^ besieged. One result of the skirmish was that “the soldiers which had been stationed in a small stockade fort, on the hill at the edge of the woods, were drawn in, the fort being so poor it was not judged proper for them to continue in it, it being so badly set up was called Fort Raskel[sic].” This fort was called Fort George on the maps. It was located about where the Castle school now stands at West Van Buren and Montcalm streets.

Stephen has little or nothing to say about the morale of the troops stationed at Oswego. In his time the common soldier was considered a very inferior kind of man with whom honest, law- abiding citizens would scorn to associate. On the other hand, an officer was a gentleman who would not demean himself by recognizing an artisan. It is likely that Stephen and his fellow workmen had little more than casual contacts with any belonging to the military. He does report on several occasions that soldiers were reported missing and that the assumption was that they had deserted. Conditions must have been bad to lead men to run away into a wilderness infested with hostile redskins.

On July 1st Col. Bradstreet arrived in Oswego with most of his fleet consisting of 696 batteaux and whaleboats loaded with pro visions and stores. The rest of the fleet arrived next day.

Battle Island Fight

The diary for July 3, reads as follows: “We launch two vessels, one a Brigg to carry 14 guns, and a Sloop to carry 10 guns. This morning Col. Brad street set out with his fleet to return; in the afternoon, we hear a fireing up the river; suppose Col. Bradstreet to be attacked. Soon after some Battos came down, with a number of wounded men, and inform[sic] they were attacked by a great number of the enemy, but our people maintained their stand, though they lost many men killed and wounded. A party of men was sent from here to their assistance, but before they arrived to the[sic] place of action, the enemy had retreated: and they returned. here, about 12 o’clock at night.”[sic]

“July 4th an express from Col. Bradstreet informs that he had lost many men, and had killed many of the enemy, had taken two Frenchmen; a number of men were sent from here, to guard him over the falls; as some trading battos[sic] were coming down the river. A Frenchman ran into the river and delivered himself to them.” This is Stephen’s complete account of the battle of “Battle Island.”

As July wore on, more and more Indians were seen about the fort. Parties were frequently sent out after them but seldom did they overtake them. On the 16th a party of friendly Indians and whites setting out for Albany came upon a large body of Indians crossing the river above the fort. On the 17th a strange Indian came to the fort. He asked to see the commandant. When he was admitted to the fort, it was noticed that he looked everything over very carefully. He told the commandant that there were others in the woods who, he believed, would come in if it were safe to do so. The commandant assured him that it was safe for them to come in. The Indian left, but instead of going into the woods went to the ships being built in the harbor and looked them over very carefully particularly[sic] counting the guns. This was reported to the commandant who ordered the Indian detained. Before the order could be executed, the Indian had escaped into the woods. Next day, however, he was discovered spying around the fort, captured, and placed in the dungeon of the fort.

Deserters Are Executed

Suspicion was mounting at the fort that the French and Indians were closing in. Boats were frequently sent to the east to try to obtain information. An express was sent out on the 23rd to the Great Carrying Place to hurry reinforcements. All the soldiers were employed in strengthening the fortifications and the carpenters in cutting timber in the woods.

From July 22nd to August 6th Stephen reports himself as being very unwell. What his illness was he doesn’t report[sic]. On Sunday, August 8th, Stephen went to church to hear the chaplain of Shirley’s Regiment preach from the text, “What Man is he that liveth that shall not see death? Shall he deliver his soul from the hand of the grave?” Psalm 89, verse 48. The occasion of this lugubrious oration was the condemnation of two American soldiers, Daniel Bean of Kingston, N. H., and Abner Tyler of Uxbridge, Mass. These two were singled out of a number who had been tried for desertion on August 4th. An effort was made to reprieve[sic] them until the findings of the court martial could be sent to General Shirley, but the commandant refused a stay. Bean was shot before his regiment at Fort Ontario; Tyler, before his regiment at Fort Oswego, the next day.

On July 22nd the scouting boats had brought word that a large body of men were about 24 miles east of Oswego. The French fleet was becoming more active in engaging any British ships they could find. On August 5th a force of 600 French and Indians was reported about 12 miles to the east and a large number eight miles east of them. Not again until August 11th does Stephen report signs of the enemy and then the curtain was rising[sic] for the last act. Montcalm’s Advance Guard At Hand On the morning of August 11th a number of boats were seen coming around Four Mile Point. A scouting boat was sent out and soon returned with the word that there was a large encampment on the bay (Baldwin’s) about one mile from Fort Ontario. That would be about the location of St. Paul’s cemetery. The boats that were in commission in the harbor, two sloops, went out to shell the camp, but they were driven off, one of them leaking badly. A sortie was made from the fort to draw attention away from the disabled craft. It was successful to the extent that the ships were able to return to the harbor. The situation at the fort was bad. Stephen says “we found our Selves[sic] in a Poor Situation to Make any defense against such an armament as we had reason to think was come against us; and had got a footing so near, and now, keep up a constant fire of small arms, from the Edge of the Woods, on Fort Ontario.” Some Indians came in and told the British that Col. Bradstreet was on this side of Great Carrying Place, but they were believed to be spies and their story disbelieved[sic].

Battle Of Oswego Opens

August 12. On this[sic] morning a large number of boats were seen coming around Four Mile Point and joining those in the bay. A constant small arms fire was kept on the fort by the French. This was returned by the fort, small arms, cannon and bombs. One man was killed and five wounded in Fort Ontario. August 13, 1756. Friday the 13th for the superstituous[sic]. Montcalm had been busy during the night. One hundred yards from the fort was an entrenchment so high that the cannon shots from the fort could not reach the French. A brisk fire was kept on both sides. The enemy was scarcely seen, but at noon 450 men evacuated Fort Ontario, crossed the river and joined Col. Schuyler in Fort George (Fort Raskel[sic] as Stephen calls it.) This fort, though Stephen doesn’t mention it, must have been strengthened and reoccupied after the withdrawal from it earlier in the summer. The French occupied Fort Ontario and immediately turned its guns upon[sic] Fort Oswego. “Fort Ontario was Fort Oswego’s defense on the River Side, which is now gone, and Nothing to Defend us that way, but the old Stone House which was called the Old Fort, but of no Consequence, Either for Bigness or Strength, against Cannon: thus we find ourselves in a pityful[sic] Situation; and no way to Retreat or Escape.”

Eye Witness Describes Battle’s Final Day August 14, 1756. Though it may seem long the climax of the story should be told in Stephen’s own words:

“On the Appearance of Daylight our Morning Gun was fired as usual, But A Shot Put in it. and pointed to Fort Ontario, Concluding the Enemy to be there; we were immediately answered by 12 Shot, from so many heavy Cannons which they had Prepared in a fasheen (fascine)[sic] Battery, on the high Bank of the River, before the fort (in the Cover of the Night) Upon which, our Guns were Briched about, on their platforms, all that Could be Brot[sic] to Bear, and as Severe a Cannonade on Both Sides, as Perhaps Ever was, until about 10 o’clock, about this time we Discovered the Enemy, in Great Numbers, Crossing the River, and we not in force Sufficient to go up and oppose them, and being Judged not safe any longer, to Keep the Men, in Fort Raskel[sic] that was Evacuated; and we all were Huddled together in and about the Main Fort, the Comadent, Coll. Manser, (Mercer) about this time was killed by a Cannon Ball; thus the man who this week had the lives of valuable men in his hands, anu would not extend Mercy to them, now had not time, not even to sue for his own life; the Enemy now appearing on the edge of the Woods, and many of our Men Killed and Wounded, and no Place of Shelter, in any Quar ter; A Council of War, was held in the Ditch; A Parley was beat, and A Flag For A truce hung out; and our Fire Stopped Upon which, the Enemys Fire also Seased; an officer Sent over with A Flag and one of their officers Came over to us; and our Com manding officer, , Proposed, to give up the fort, on Conditions of their Giving us leave to March off Unmolested; with our arms and two Pieces of Cannon: this was Refused, and no Other Terms would they acceed to, bui our Delivering up the fort, with all the Stores, and we to be Prisoners of War, and to be sent to Canada; at length this was Accepted; and an officer Came ovei to take Possession, the Can adians and Indians, came flock ing in from All Sides, we were all ordered to cross the River, and put ourselves under the Pro tection of the french Regular army; thus, this Place fell into the hands of the French; with a Great Quantity of Stores, we suppose about 9000 Barrells of Provisions, A Considerable Num ber of Brass and Iron Cannon, and Morters; one Vessel! just Launched, two Sloops Peirced[sic] for 10 Guns each, one Schooner Peirced[sic] for 10 Guns, and one Row Galley, with Swivels, and one Small vessell[sic] on the Stock about (Half Built, A great Number of Whailboats[sic], and as Near as I can Judge between 14 & 16 hundred, Prisoners; Including Soldiers, Sailers, Carpenters, and the Army to which we Surrendered, Consisted of 5 Regiments of Regular Troops, anu about 1000 Canadians, and Indians, with an Artilery[sic], Consisting of 40 Peices[sic] of Cannon, besides Morters[sic] and Howitzers, mostly if not all Brass, and it is Laid to be the Artilery[sic], which was taken from Gen. Braddock, at the Ohio; on going over to the French Army, we was ordered into fort Ontario, which was Made our Prison for the Present; and A Guard Set Round us, for two Reasons, one to Prevent our Stragling[sic] off, and another, to Prevent the Indians from Murthering[sic] us: as we Understood, they had all the Sick, and Wounded, and those who instid[sic], of Coming directly over the River to the French Regular troops, went to the Setlers[sic], and traders Houses, and Intoxicated themSelves[sic] with liquor.

French Regulars Prevent Massacre

This Army was Commanded by General Montcalm; all those who obeyed the orders, and Crossed the River, to the French Army, was verry[sic] well Used; Some of our Soldiers, before they Came over, went to the Stone Houses, and filled their Canteens with Rum and Asoon as they were Got Safe into fort Ontario, under the French Guards; began to Drink and Soon Got Intoxicated, and Soon began fighting, with one another; while others Sing ing, Dancing, Hollowing, and Ca hooping. that it appeared More like a Bedlam, than A Prison; Soon after the Indians had gov into our fort, they went Searching for Rum; which they found, and began to Drink, when they Soon became like so Many hel Hounds[sic]; and after Murdering and Scalping, all they Could find on that Side, Come over the River with A Design, to do the Same to all the Rest; and oft their Coming Near the Fort where we was, and hearing the confused noyes of those within; United their Hideous Yells and Rushed the Guards Exceeding hard, to git in among us, with their Tomahawks; and it was with Great Difficulty the French, Could Prevent them; in the Evening Some French officers, Come into the Fort, and told us, excep[sic] we would be still, they Could not Keep the Indians out, from us, and Must, and Would, take off their Guard, for they were so Raveing[sic] distracted, by hearing ower[sic] nois[sic], that Except we were Still, they must give us up; but all Signefied[sic] Nothing. our Drunken Soldiers Continued their Noyes, and the Indians, their Strugles[sic] and Yelling, Until the operations of the Liquor, together with the Strong Exercions[sic], began to dispose boath[sic] Parties to Sleep, which about 12 oc Clock took Place, and to our great Joy, all was Quiet.”

Thus did Montcalm deal the English a severe blow that probably prolonged the war. The French lines of communications to the west were secure.

Prisoners Taken To France

Stephen and his companions were taken as prisoners of war to Canada and then to France, but that’s another story of adventure and hardship that must be told some other time.

For those who like to read the last page before finishing the book, I’ll close with a statement by Miss Sarah E. Milliken who wrote the introduction’ to the diary as we now have it:

“Stephen Cross was a typical Yankee of his age and generation, fervent in spirit and in the Presbyterian church, by no means slothful in business—his shipyard and his distillery prospered,. He was collector of customs and at the time of his death he was postmaster for Newburyport. During the Revolutionary War he was on many important committees, both in the town and commonwealth. He and his brother built three frigates, the Hancock, the Boston, and the Protection, and Tie was also prominent in town affairs, being one of the first selectmen of Newburyport and a representative to the general court. When John Mycall[sic] printed for the Rev. John Bennet, letters to a young lady on a variety of useful and interesting subjects, Stephen Cross’s name was among the subscribers. After reading the account of his terrible experiences as a prisoner, it is pleasant to remember that he lived to a good old age, honored by his townspeople. His house, backed by a pleasant garden, faced the blue Merrimac and the distant bar, and from his front windows, he could see his well filled warehouses, his wharf and the white sails of his ships coming up the river. All around him were kinsfolk and friends, and his life as a prisoner must have seemed a dreadful nightmare.”