“This essay was originally published in the 1940 OCHS Yearbook. Please note that this essay was published over 84 years ago. While still useful for general education, language may be outdated and at times offensive. The Oswego County Historical Society does not stand by the language used in this essay. All photos were added in 2024 when this article was uploaded to the web. To view the original document, please visit NYHeritage.org.”

(Address Given Before Members of the Oswego Historical Society, November 26, 1940, by Dr. Edward P. Alexander, Director of the New York State Historical Association)

In the Fall of 1790, one hundred and fifty years ago, William Cooper decided to remove his family from their neat home in Burlington, New Jersey, into the wilderness of Central New York. But William Cooper’s wife, Elizabeth, was a somewhat strong minded woman who did not relish the prospect of leaving civilization for the western frontier. When the time came to depart, she sat herself down in her chair and refused to budge from it, whereupon her equally determined husband had the chair, wife and all, loaded upon the wagon. More significant than this amusing family tradition is the fact that Mrs. Cooper brought with her to Cooperstown a year-old[sic] baby boy named James.

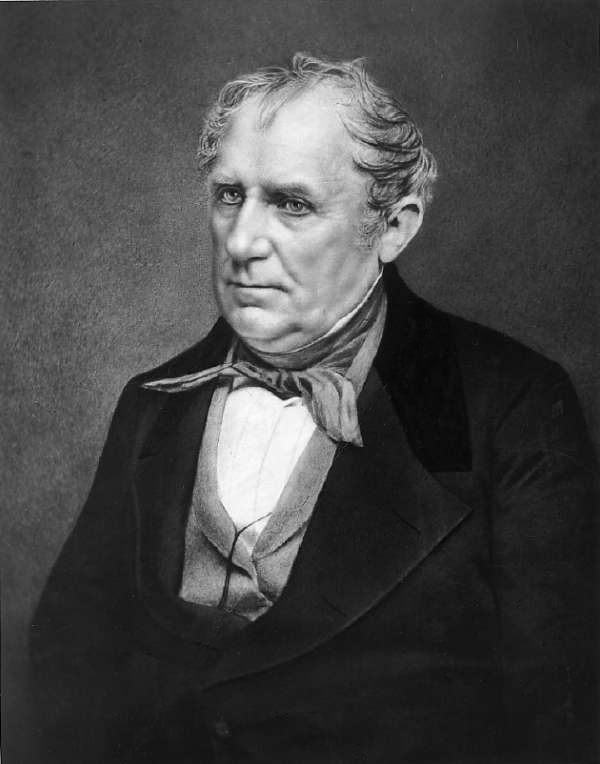

This boy grew to manhood in Central New York, and he brought the region and, indeed, the whole State immortality with his great stories. But, unfortunately, his reputation suffered somewhat in later days. Part of the responsibility for this fact lies with Cooper himself. Perhaps a little sore in spirit after his encounters with the newspapers of the day, he requested his family not to authorize a biography. Thus when Thomas Lounsbury wrote his ex cellent “James Fenimore Cooper ” in 1882, he was forced to work without access to the personal papers of the novelist. Professor Lounsbury’s book still remains a classic of biography, and his judgment of Cooper’s literary merit is undoubtedly sound, but he was too often forced to evaluate Cooper’s personality through what the newspapers said, without benefit of Cooper’s frank and colorful personal letters. Thus the impression has arisen that Cooper was most harsh, snobbish, and irascible.

In 1897 Mark Twain set out to demolish Cooper’s reputation as a literary craftsman in an article entitled “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offences.” This analysis dwelt upon the heaviness of Cooper’s style and upon such slips as the one in “The Path finder” of having Natty Bumppo[sic] see a bullet enter a target one hundred yards away.

Inventive Mind Talent Source

But such criticism is unfair in that it ignores the fact that Cooper’s great talent lay in invention— the creation of intricate plots and heroic characters —and not in subtle characterization and style. He also usually was his own editor and did not have the advantage our modern novelists enjoy of having the obvious slips eliminated by skilled editorial minds. Cooper was a hard worker, who wrote nearly every day, no matter how he felt or whether he was in the mood. He was a great ex temporizer, and the genius of his creative imagination is not damaged by superficial flaws.

There can be no doubt of Cooper’s just claim to fame as a storyteller. A novelist should be judged somewhat by the standards of his day, and the novel of the time in which Cooper’s work appeared was a weak thing, filled with sentimentalism, melodrama, and moralizing, all written in an extremely stilted style. Its chief audience consisted of romantic young “females,” who shed tears over the misfortunes of the heroine and shuddered be fore what Carl Van Doren has 101 called “the unceasing menace of the seducer.” Cooper’s books with their American background and fast-moving action were fresh, original, and even comparatively simply written.

Another test of a novelist is his ability to create a great character that will live forever. If any American were asked to name ten great characters of our literature, he would at once think of Leatherstocking, or Natty Bumppo[sic]. It is ever a matter of surprise to Americans how much Cooper is read abroad. He has always been more popular with the French than has Sir Walter Scott; Balzac had some very glowing things to say about “The Pathfinder;” and one French statesman, on hearing of the entrance of America into the World War in 1917, said, “The Spirit of Leatherstocking still lives on.” Of course, as William Lyon Phelps points out, every time Cooper was translated, he was improved, because superficial errors of style were eliminated.

Cooper Now Better Understood

Cooper is also coming to be better understood as a personality. James Fenimore Cooper, the grandson of the novelist, generously gave a large collection of Cooper’s papers to Yale university and edited the two volume[sic]”Correspondence of James Fenimore Cooper,” which Yale published in 1922. Since that time three books, making use of the Yale manuscrips[sic], have appeared to change our former evaluation of Cooper—Henry Walcott Boynton’s “James Fenimore Cooper” (1931); Professor Robert E. Spiller’s “Fenimore Cooper; Critic of His Times”[sic] (1931); and Dorothy Waples[sic]’ “The Whig Myth of James Fenimore Cooper” (1938). This fresh work throws new light on the novelist and makes one realize that, despite “a certain emphatic frankness in his manner” and his “always bringing a breeze of a quarrel with him,” he was to those who knew him, a loyal, even sentimental, friend, a fascinating conversationalist, and an inspiring companion. The tact rind of the man’s personality but added to his humanity.

Young James Cooper grew up on the western frontier of the day. There were bears, wolves, and panthers in the forests of Otsego, and even an occasional Indian. There was also one “Ship-man, the ‘Leather Stocking’ of the region, who could at almost any time, furnish the table with a saddle of venison.” But though Cooper lived on the frontier, where he could know its color and hear its stories, he was the son of the “manor lord” of the region, Judge William Cooper, and thus provided with enough leisure to use his imagination and give thought to what he saw and heard.

In about 1800 young Cooper was sent to Albany to study under the Rev. Thomas Ellison, rector of St. Peter’s church. There he grew to know the young Van Rensselaers and other scions of old New York State families. In 1802 at the age of thirteen he entered Yale but became involved in several mischievous college scrapes and was expelled during his Junior year. So far as his future career went, this dismissal was no catastrophe, because the colleges of that day were not teaching men to write well, and Cooper’s experiences during the next two years were much more valuable to him.

The young man decided he wished to join the United States Navy, and since there was then no Annapolis to train midshipmen, in the Fall of 1806 he shipped on the “Sterling,” of Wiscasset, Maine, Captain John Johnston. The “Sterling” went twice to London and also encountered a Moorish pirate felucca in the Mediterranean. Such adventures gave Cooper a great love for the 102 sea, and he was glad to receive his commission as midshipman, January 1, 1808.

Cooper’s Activity At Oswego

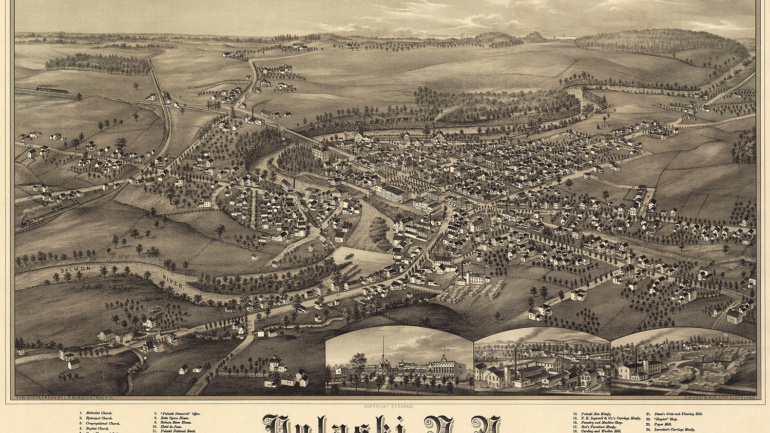

In the Fall of 1808 Cooper was one[sic] of a small party under Lieutenant Melancthon[sic] T. Woolsey sent to Oswego on Lake Ontario. Lieutenant Woolsey was directed to build the “Oneida,” a brig-of-war of 240 tons, pierced for 16 guns, for service on Lake Ontario in case the unfriendly relations then existing between Great Britain and the United States should result in war. Two smaller gunboats were also to be built by Woolsey on Lake Champlain.

The arrival of five naval officers and a gang of carpenters, blacksmiths, and other workers gave Oswego, then a village of a score of houses on the West side of the Oswego river, a great thrill, and during the Winter a small detachment of infantry under Lieutenant Christie arrived at the old Fort Ontario. Life at Oswego was generally dull, and Cooper and his friends amused themselves with such pranks as crawling out on the roof of their neighbor’s house and dropping snowballs down his chimney.

The launching of the “Oneida ” was celebrated with a frontier ball. Ladies were hard to find, but by sending boats miles in one direction, and carts miles in another, enough of them were gathered to make the affair a success. A delicate question of etiquette then arose—how should the position of the ladies in the dances be determined? Lieutenant Woolsey solved the vexatious problem as follows: “All ladies, sir, provided with shoes and stockings, are to be led to the head of the Virginia Reel; ladies with shoes and without stockings are considered in the second rank; ladies without either shoes or stockings you will lead, gentlemen, to the foot of the country-dance.”

Midshipman Cooper remained in charge of the brig at Oswego early in June, 1809, when Lieu tenant Woolsey went to Lake Champlain to look after the gun boats, but on the latter’s return in September, the two set out with a small party in a launch on a journey to Niagara Falls. Food ran low during the trip, but Cooper killed a hedgehog with the sword of a cane, and Woolsey diplomatically persuaded a transplanted London Cockney to sell them a sheep, silencing the wife’s protests by praising her fine children, “three as foul little Christians as one could find on the frontier.”

Material for Pathfinder Gathered Here

But Cooper was restless at the prospect of another Winter in Oswego, and in September he sought a furlough to take a trip to Europe. His request was granted, and he left Oswego, but in November relinquished his planned journey and instead did salt-water duty in the man-of-war “Wasp,” Captain James Lawrence. After a Winter on this vessel, Cooper took a furlough because of his father’s death.

His stay in Oswego furnished Cooper with a knowledge of the region which he later used in “The Pathfinder,” one of the Leatherstocking Tales. Cooper himself regarded it as one of the best things he had ever written, and Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant, Herman Melville, and Balzac all praised it very highly. The book was published almost simultaneously in England and America in 1840. It was written in Cooperstown and Philadelphia during 1839. A good commentary on Cooper’s writing habits is the statement in his letter from Philadelphia to Mrs. Cooper, October 19, 1839: “The first volume of “Pathfinder” is printed—the second is not yet written.” Another letter of December 19 shows that he had 103 nearly completed the work. In its first two months, “The PathFinder” sold nearly 4,000 copies, a “great success, in the worst of times,” as Cooper wrote.

The fate that so frequently overtakes a young man soon befell Cooper. As he wrote: “Like all the rest of the sons of Adam, I have bowed to the charms of a fair damsel of eighteen. I loved her like a man and told her like a sailor.” James Cooper was married to Susan DeLancey on January 1, 1811, and Susan, not relishing having her husband away on long and dangerous sea voyages, persuaded him to resign from the Navy. In a way it is too bad he did not continue his naval career. He was a most ac tive and decisive person and should have gone far in the Navy during the War of 1812.

How First Book Was Written

The secret of Cooper’s career is his remarkable energy. Though the estate left him by his father and the inheritance of his young wife (The De Lanceys[sic] were, of course, one of the great families of colonial New York ) would have allowed him to coast through life in easy fashion, he soon tired of the life of a country gentleman and restlessly sought an outlet for his energies and talents. He plunged into farming at Cooperstown and in 1817 served as secretary of the Otsego County Fair, the first county fair in the State. In 1818 he purchased a two-thirds interest in the “Union,” which went whaling from Sag Harbor to the coasts of Brazil and Patagonia, and he frequently went to Sag Harbor to busy himself with re-fitting the “Union’ ‘and marketing whale oil.

But in 1819 while the “Union” was filling her hold with whale oil, the incident took place which changed Cooper’s whole future. He was reading a poor English novel to his wife, when, becoming disgusted with its trashiness, he exclaimed: “I could write you a better book myself.” When Susan De Lancey[sic] Cooper laughed at the idea with true wifely scorn, Cooper sat himself down and began to write a novel about English drawing-room society, called “Precaution,” published in 1820, and probably one of the dullest novels ever written.

Many people have set out to write books; a few have completed a single work; but very few have ever written a second one. Cooper, however, persevered, and in 1821 he published the first great American novel —The Spy. This book dealt with the American Revolution in Westchester County, a topic and setting which Cooper thoroughly understood. Two years later Natty Bumppo[sic], or Leatherstocking, was introduced to the world in “The Pioneers,” whose setting is Cooperstown and Otsego Lake. In that same year (1823) appeared “The Pilot,” a new literary type—the tale of adventure on the sea with accurate nautical details. All three of these works were remarkable successes. During the remainder of his life, Cooper systematically wrote novels, critical essays, books of travel, and histories; when he died in 1851, fifty-two works were credited to him.

The Bread and Cheese Club

In 1822 Cooper moved to New York City, where he organized the Bread and Cheese Club, sometimes called The Lunch, or Cooper’s Lunch. The chief men of the day drawn from every walk of life belonged to this literary club, men like Fitz Greene Halleck, William Cullen Bryant, Samuel F. B. Morse, William Dunlap, James Ellsworth De Kay, and Chancellor James Kent. Cooper was affectionately referred to as “The Constitution” of the club, and we have two excellent descriptions of him during this period.

William Cullen Bryant, the poet, writes thus of him: 104 “I remember being struck with the inexhaustible vivacity of his conversation and the minuteness of his knowledge in everything which depended upon acuteness of observation and exactness of recollection. I remember, too, being somewhat startled, coming as I did from the seclusion of a country life, with a certain emphatic frankness in his manner, which, however, I came at last to like and to admire.”

Lawrence Godkin[sic], also a member of the Bread and Cheese Club, was impressed by the contrast between Cooper and Bryant: “Cooper burly, brusque and boisterous, like a bluff sailor, always bringing a breeze of quarrel with him; Mr. Bryant shy, modest, and delicate as a woman —they seemed little fitted for friendship. Yet Bryant admired not only the genius, but the thorough paced honesty and sturdy independence of Cooper; and Cooper . . . once said, ‘We others get a little praise now and then, but Bryant is the author of America’.”

Friend of Scott and LaFayette[sic]

In 1826 the Cooper family left New York for Europe, and during the next seven years the novelist resided abroad. He was treated as a literary lion, met Sir Walter Scott, and became a close friend of the aged LaFayette[sic]. He wrote constantly and took the lead in liberal movements, such as trying to obtain a Polish Republic.

Cooper was a patron of the arts, who lent money to struggling painters and sculptors, introduced them to prospective patrons, and sometimes gave them small . commissions. On March 16, 1832, he wrote his friend William Dunlap a letter concerning his daily life and his good friend Samuel F. B. Morse, which runs as follows:

“I get up at eight, read the papers, breakfast at ten . . . work till one—throw off my morning gown, draw on my boots and gloves, take a cane that Horace Greenough gave me, and go to the Louvre, where I find Morse stuck up on a high working stand, perch myself astraddle of one of the seats and bore him just as I used to bore you when you made the memorable like ness of St. Peter. ‘Lay it on here, Samuel—more yellow—the nose is too short—the eye too small —damn it if I had been a painter what a picture I should have painted.’—and all this stuff over again which Samuel takes just as good-naturedly as good old William. Well there I sit and have sat so often and so long that my face is just as well known as Vandyke on the walls. Crowds get round the picture, for Samuel has quite made a hit in the Louvre, and I believe that people think that half the merit is mine. So much for keeping company with one’s betters. At six we are at home eating a good dinner, and I manage to get a good deal out of Morse in this way too.”

Champion of American Life

But, most important of all, Cooper dared to defend the American form of government and American way of life everywhere he went. This was considered poor taste by most Europeans who were sure that their culture was far superior to that of the materialistic and uncouth Americans. Cooper even did not hesitate to support Lafayette’s statement that a democracy was more economical than a monarchy. Not only did certain foreign newspapers criticize him harshly, but the Whig papers in the United States, disliking his expressed admiration for and defence[sic] of some of President Andrew Jackson’s measures, began to join in the critical chorus.

It is useless to argue whether Cooper’s controversies arose because he was abnormally sensitive to criticism or because his active nature led him to enjoy a good fight[sic] The fact is, that [sic]upon his return to America in the Fall of 1833, he found the country he had been defending abroad seemed changed. He thought ho saw excesses of democracy and vulgarity of taste about him, and he characteristically decided to do what he could to remedy the situation. For a time he stopped writing romances and began to produce social tracts; he became “the critic of his times.” Undoubtedly America needed some such criticism but its author brought a flood of abuse upon himself.

Sued Greeley for Libel

In those days newspapers were rarely sued for libel, and editors said what they pleased about literary productions, not confining their remarks to the merits of the books but daring to cast aspersions upon the characters of the authors themselves. As soon as this sort of criticism began to appear about Cooper, he determined to fight the editors in the courts. Systematically and carefully he prepared his cases with the assistance of his nephew, Richard Cooper, and he sued the leading editors of his day—Horace Greeley, Thurlow Weed, William Leete Stone, James Watson Webb, and others. In all of these cases, save one, he won damages or secured a retraction from the defendants and the cases firmly established the enforcement of the libel law of New York State.

Despite his quarrels with the press. Cooper’s everyday life remained serene. The Coopers had returned in 1834 to Otsego Hall, the home built by Judge William Cooper at Cooperstown in 1798 There the novelist wrote much of his social criticism, but also many of his finest romances, including The Pathfinder and The Deerslayer. Usually he wrote in his Gothic library each morning ’till about eleven, when he would drive to his farm, the Chalet, on the east side of Otsego Lake, his wagon drawn by Pumpkin, his faithful old horse, and filled usually with the children of the neighborhood. Frisk, his little black dog, would protect the expedition from the rear. Seraphina, his cow, was also well known in the village, for she persisted in trying to get into the garden at the Hall.

Argued Much with Nelson

Many people in the village disliked Cooper, especially at the time of the Three Mile Point controversy, but they listened with awe when he and Justice Samuel Nelson of the United States Supreme Court, another of Cooperstown’s famous men, exchanged opinions before the pot-bellied stove of the village hardware store. Old Nancy Williams liked Cooper, too, though she sometimes called to him as he passed her doorway, “James, why don’t you stop wasting your time writing those silly novels, and try to make something of yourself?”

In his own home Cooper was much beloved. He was always making little jokes, and his humanity is illustrated by the frequent entries in his diary concerning his games of chess with his “Dearest Sue.” One of these runs: “Chess, wife beat me in one of her slapping games, but I beat her two afterwards. One of these beats puts her in good spirits for a whole evening, and I delight to see it.”

Today, then, we are beginning to evaluate Cooper as a man. We are coming to understand his personality better, to appreciate his rugged strength, his courage, and his honesty. Perhaps, after all, Herman Melville was right when he wrote in 1852: “A grateful posterity will take the best care of Fenimore Cooper.”